|

|

Post by Cheeseman on Aug 7, 2022 20:42:07 GMT -5

Good news - the "heatwave" this week has been downgraded ever so slightly for my location. No 30 degrees any more. That BS can stay in the tropics where it belongs. Send it over here. I'm sick of the chill already. Technically the high today was 81 F (27 C) but that was at midnight. It's been in the 60s ever since about 10 AM - so a "warmer than average" day on a technicality only. |

|

|

|

Post by Beercules on Aug 7, 2022 22:14:03 GMT -5

Good news - the "heatwave" this week has been downgraded ever so slightly for my location. No 30 degrees any more. That BS can stay in the tropics where it belongs. Send it over here. I'm sick of the chill already. Technically the high today was 81 F (27 C) but that was at midnight. It's been in the 60s ever since about 10 AM - so a "warmer than average" day on a technicality only. That's the standard running gag in Melbourne in crummer. Hot day, hot night, then arctic sneeze n snot blue waffle furry mould infection the next day.  |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Aug 8, 2022 12:18:33 GMT -5

Good news - the "heatwave" this week has been downgraded ever so slightly for my location. No 30 degrees any more. That BS can stay in the tropics where it belongs. It's just a shame the rubbish can't disappear from the south too and they get rain instead. It's tinder dry down there and there'll be more houses going up in flames this week. It looks like London will have possibly 6 days in a row of 30c+, with 3 of those in the mid 30s. No rain in the forecast of course. |

|

|

|

Post by rozenn on Aug 8, 2022 12:47:00 GMT -5

29.1/16.2°C (84/61°F) today, which is confortably above average. Yet to me it felt coolish in the afternoon and downright chilly in the morning due to the wind and low dews.

|

|

|

|

Post by Met.Data on Aug 11, 2022 6:20:07 GMT -5

Cobweb season is well and truly here. Not seen so many huge webs since the warm summer of 2018. On my way back from the pharmacy earlier, I walked under a huge cobweb just above head height, spanning across the pavement from a tree to a bush on the other side. It was about 2 meters wide, and massive. I saw numerous other giant cobwebs at least 4-6ft across in various places. You have to be careful you don't walk into one. I only noticed the one across the pavement earlier on the way back as the light made it hard to see going out.

|

|

|

|

Post by greysrigging on Aug 13, 2022 16:52:03 GMT -5

August ( as usual ) has been extremely variable in Alice Springs, with temps swinging between summer and winter.  |

|

|

|

Post by dunnowhattoputhere on Aug 13, 2022 17:29:47 GMT -5

Cobweb season is well and truly here. Not seen so many huge webs since the warm summer of 2018. On my way back from the pharmacy earlier, I walked under a huge cobweb just above head height, spanning across the pavement from a tree to a bush on the other side. It was about 2 meters wide, and massive. I saw numerous other giant cobwebs at least 4-6ft across in various places. You have to be careful you don't walk into one. I only noticed the one across the pavement earlier on the way back as the light made it hard to see going out. My house has been infested with spiders all summer. Especially cellar spiders (Americans call them daddy long legs I think). I don’t mind spiders though so I usually just leave them to it. |

|

|

|

Post by Met.Data on Aug 13, 2022 18:31:31 GMT -5

Cobweb season is well and truly here. Not seen so many huge webs since the warm summer of 2018. On my way back from the pharmacy earlier, I walked under a huge cobweb just above head height, spanning across the pavement from a tree to a bush on the other side. It was about 2 meters wide, and massive. I saw numerous other giant cobwebs at least 4-6ft across in various places. You have to be careful you don't walk into one. I only noticed the one across the pavement earlier on the way back as the light made it hard to see going out. My house has been infested with spiders all summer. Especially cellar spiders (Americans call them daddy long legs I think). I don’t mind spiders though so I usually just leave them to it. Same here in fact, earlier I found that a bunch of spiders had made webs around my bed, and there was also one crawling about inside my bed for some reason. |

|

|

|

Post by Babu on Aug 17, 2022 6:18:53 GMT -5

This year has been absolutely wild on the SE Swedish island Öland. Every month has been a fair bit above average apart from April and May, with the summer months in particular being consistently among the warmest in the country. And look at the rainfall, extremely dry year! Also looks absurd how the weather changed between April and June.  |

|

|

|

Post by Babu on Aug 17, 2022 6:37:49 GMT -5

July was below average outside of the SE, so for that reason Örebro and Stockholm don't look quite as impressive as they could have.   Gladhammar in the SE has had very consistently warm highs throughout almost the entire year. Unfortunately though they have a few missing days in August...  |

|

|

|

Post by Met.Data on Aug 17, 2022 10:33:03 GMT -5

Two weeks until Autumn. Looking forward to it already.

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Aug 24, 2022 20:59:13 GMT -5

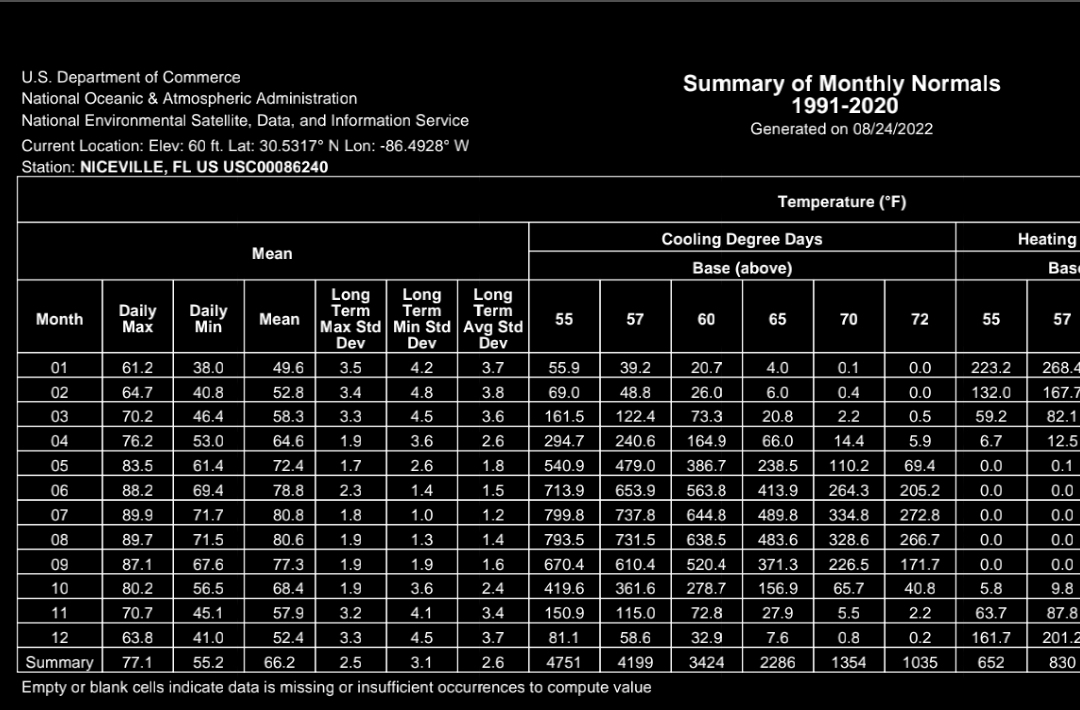

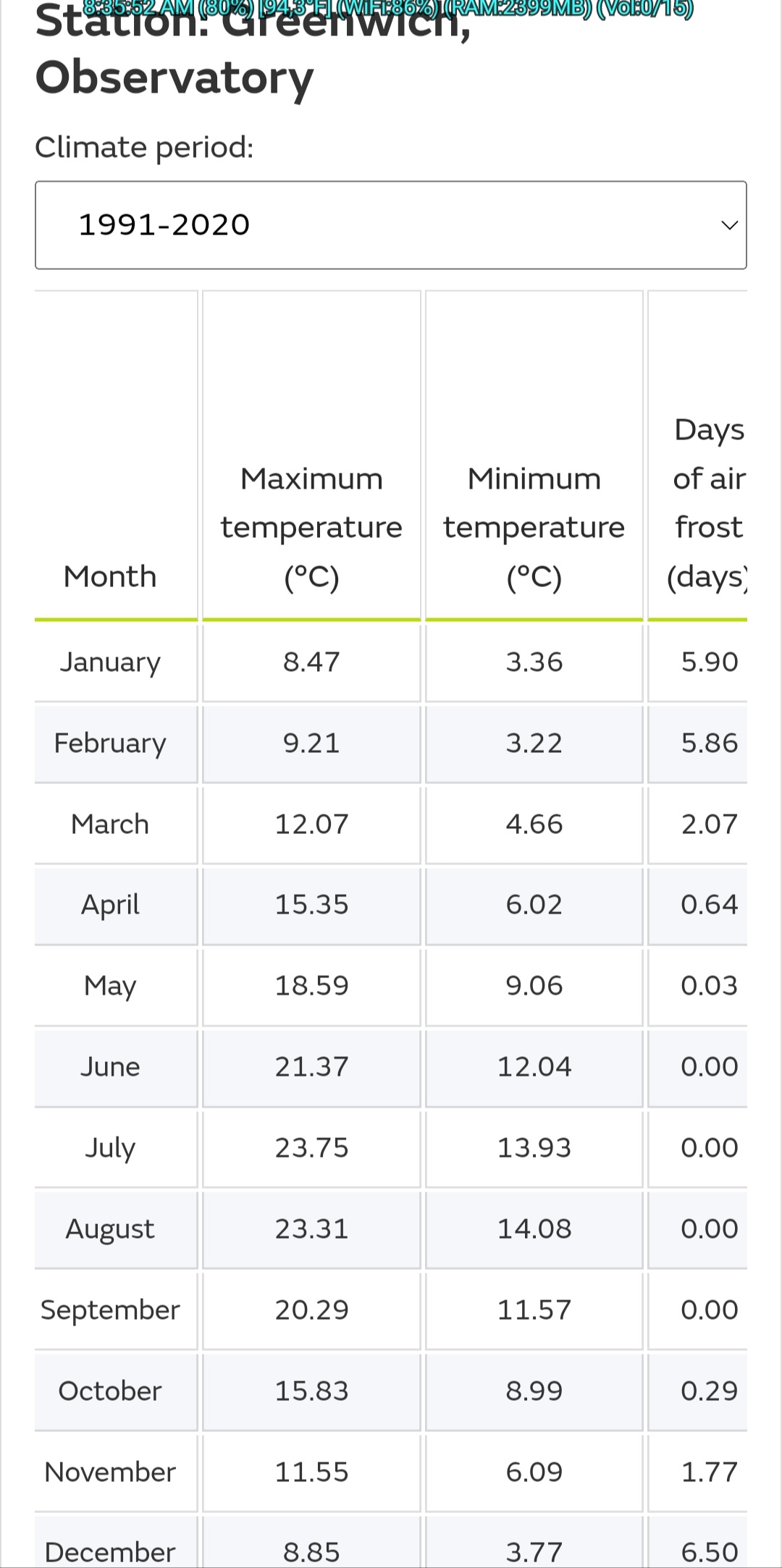

The January average low in Niceville, FL is a hair cooler (38.0°F vs 3.36°C/38.05°F) than that of London, UK at the Greenwich station as per the 1991-2020 normals. Niceville, FL London (Greenwich), UK London (Greenwich), UK

|

|

|

|

Post by greysrigging on Aug 25, 2022 4:59:00 GMT -5

Where Is The Lightning Capital Of Australia ? ( source: Weatherzone )  Australia is a stormy country, with lightning striking part of every state and territory each year. But some parts of the country are far stormier than others. So, where is the most lightning-prone part of Australia? Before looking at WHERE lightning occurs in Australia, it’s important to know HOW lightning occurs. Thunderstorms require three key ingredients to form: Moisture-laden air in the lower levels of the atmosphere Instability in the atmosphere, which means temperature cools sufficiently with height A trigger mechanism, which is something that causes air to start rising or lifting The stormiest places in Australia, and the world, are simply areas that have these three ingredients available in abundance. The map below shows the annual average lightning density across Australia. Lightning density here represents the average annual number of lightning pulses per square kilometre that were detected by Weatherzone’s Total Lightning Network between 2015 and 2021.  Before we dig into the numbers to find out where Australia’s stormiest place is located, there are a few interesting things that stand out on the map above at first glance. Lightning occurs more frequently near the coasts and ranges in an upside-down horseshoe shape. This is because these areas have abundant moisture and the mountainous terrain helps initiate thunderstorms. Sea breezes also act as a frequent thunderstorm trigger in near-coastal zones, especially in northern and eastern Australia. Central and far southern Australia are lightning-sparse, largely because these areas lack the moisture and/or instability needed for frequent thunderstorms. Eastern Australia has a broad area of dense lightning activity that stretches from southeast QLD down to central NSW. This region is often at the confluence of warm and moisture-laden air coming from the north or east, and colder air moving in from the south or west. These contrasting air masses can give rise to violent thunderstorm activity, especially during spring and summer.  Another lightning hotspot is over far northern Australia, including portions of northwest QLD, the western Top End and the northern Kimberley. While these areas are predominantly dry and storm free for around half of the year, they become hotbeds for thunderstorms in the wet season.  The map above also shows that Australia’s most lightning-active area, based on observations from the last seven years, is located over the western Top End, to the east of Wadeye. This region, which roughly lies over the Nganmarriyanga community, experiences close to 200 lightning pulses per square kilometre per year. Of the capital cities, Darwin is Australia’s stormiest capital city, experiencing around 54 lighting pulses per square kilometre per year. This is followed by Brisbane (26), Sydney (18), Canberra (16), Melbourne (8), Perth (4), Adelaide (3) and Hobart (1). There is also a distinct seasonality to Australia’s lightning activity. The four maps below show how much lightning density changes, in both storm location and frequency, at different times of year.     |

|

|

|

Post by Beercules on Aug 25, 2022 5:59:32 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by Ariete on Aug 25, 2022 9:14:15 GMT -5

Autumn is coming to Northern Lapland:

|

|

|

|

Post by jgtheone on Aug 27, 2022 5:07:31 GMT -5

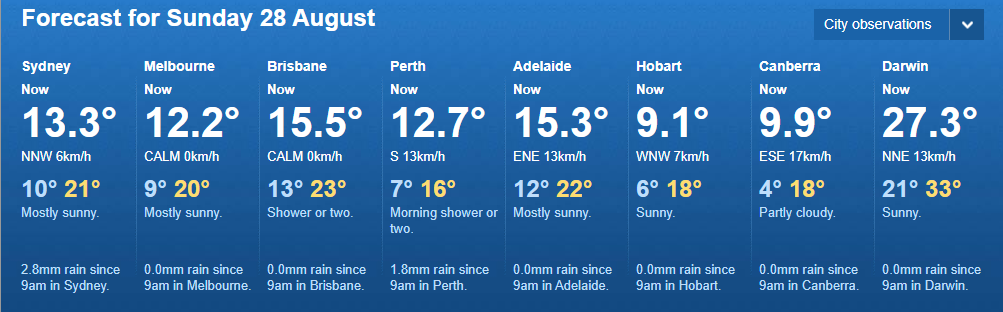

Perffffff will be the coldest capital city tomorrow.  |

|

|

|

Post by greysrigging on Aug 31, 2022 22:44:23 GMT -5

Winter has returned with a vengeance to Alice Springs today ! Biting cold and wet   |

|

|

|

Post by Crunch41 on Sept 1, 2022 7:46:59 GMT -5

A spot near Wadeye gets 4 times the lightning of Darwin. That's impressive, Darwin seems to get a lot already.

|

|

|

|

Post by nei on Sept 15, 2022 18:47:58 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by greysrigging on Sept 21, 2022 2:30:18 GMT -5

La Nina - What is La Nina and how does it impact weather?  La Niña is a natural phenomenon that has a significant impact on weather and climate all over the world. So let’s find out what La Niña is and how it affects the weather in Australia. What is La Nina? La Niña is a broad-scale circulation in the Pacific Ocean that is characterised by warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures to the northeast of Australia and abnormally cool water in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. The warm oceans and humid atmosphere that are associated with La Niña typically cause increased convection over the western side of the tropical Pacific Ocean. This in turn drives above average rainfall and cloud cover across much of Australia.  La Niña is one of three phases of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, with the other two phases being El Niño and neutral (neither La Niña nor El Niño). La Niña events typically begin and end around the Southern Hemisphere’s autumn and have the greatest impact on Australia’s weather between winter and early-summer. On average, La Niña occurs roughly once or twice per decade, with around half of La Niña events occurring back-to-back over consecutive years. It is rare to see three consecutive La Niña events – this has only happened three times since 1950 (1973 to 1976 and 1998 to 2001). What causes La Niña? La Niña is known as a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon, which means that once it is underway, the ocean and atmosphere reinforce each other. As a result, and unlike some other climate drivers that affect Australia, La Niña typically persists across several consecutive seasons. La Niña occurs when the temperature contrast that develops across the equatorial Pacific Ocean supports stronger trade winds blowing from east to west across surface of the Pacific. These enhanced trade winds cause warmer-than-average water to pile up on the western side of the equatorial Pacific Ocean and cooler-than-average water to form in the central and western equatorial Pacific. These pools of abnormally warm and cool water help air rise over the western Pacific Ocean and sink on the eastern side of the Pacific basin. This rising and sinking air causes enhanced convection and cloudiness near Australia, and reduced cloudiness over the central eastern Pacific Ocean. What are the effects of La Niña? The warm oceans and humid atmosphere that are associated with La Niña typically drive above average rainfall and cloud cover across much of Australia, especially between winter and early summer.  The increased cloud cover and rainfall during La Niña also promotes cooler-than-average daytime temperatures across Australia, but warmer than average night-time temperatures. Heat extremes are generally less frequent during La Niña years, while prolonged spells of lower-intensity heat are generally more common. The warm oceans near northern Australia make La Niña favourable for tropical cyclone development. La Niña also increases the likelihood of an earlier-than-usual start to the cyclone season and Australia’s northern wet season.  During La Niña years, the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) usually remains in a predominantly positive phase. This typically promotes rainfall in eastern Australia, while reducing the frequency of strong wind and thunderstorm events in the south and east. The broad-scale influence of La Niña on the ocean and atmosphere affects weather patterns around the world. For example, while rainfall typically increases over Australia during La Niña, parts of North America often experience more bushfires and drought.   What is the difference between El Niño and La Niña? When La Niña is not occurring in the Pacific Ocean, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is either in a neutral phase of in El Niño. Neutral ENSO conditions mean that the Pacific Ocean is not having a major influence on the weather or climate in Australia or the rest of the world.  El Niño is opposite to La Niña in its causes and impacts. El Niño is characterised by cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures to the northeast of Australia and abnormally warm water in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. The cool oceans and drier atmosphere that are associated with El Niño typically cause decreased convection over the western side of the tropical Pacific Ocean. This in turn drives below average rainfall and cloud cover across much of Australia.  |

|